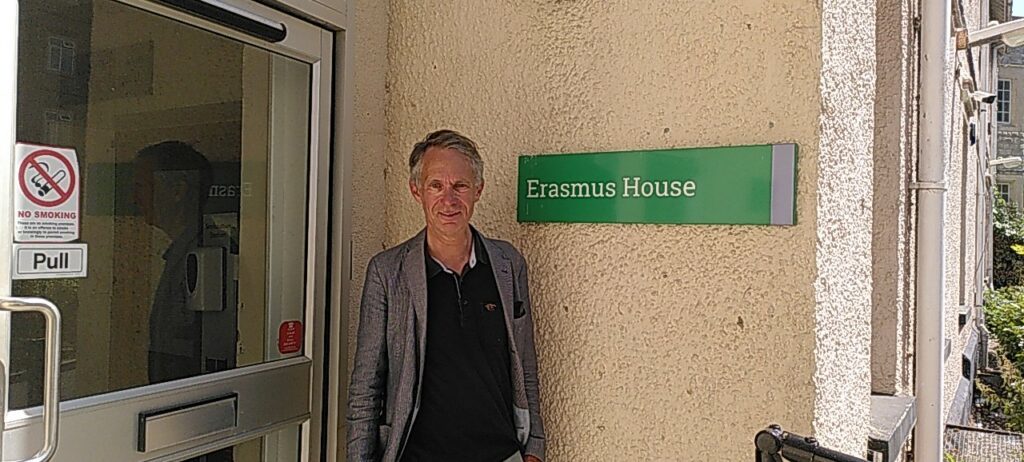

“We are always happy to host guests when we can and encourage people who are interested in popping over to visit the college however in this instance, I’m not sure a visit to us will meet your hopes laid out below. Though we do have an administrative building named Erasmus, there is little other connection and after speaking with our archivists, I’ve been assured there is little for you to see linked to your project, ” Ginny Jordan-Arthur writes to me in response to my plan to visit Erasmus House at the University of Roehampton in south-west London.

On Thursday 8 June, I arrive in Roehampton by bike. Julia Tomas is waiting for me there. What does she know about Erasmus? For instance, that he was upset when he was given beer but not wine to drink at Oxford. A new story for me, but fitting with Erasmus’ theory that red wine would reduce his kidney stone complaints. The building was named after Erasmus some 20 years ago. I hear from Julia and some other visitors that the university was originally Catholic and all buildings were named after priests. Nowadays, what counts more is that the namesake must have been an exemplary figure. For instance, one building was renamed after Mandela and a building was named after an African nurse in a war zone.

Of course, I think Erasmus is pre-eminently an example both as a teacher and as a moral compass, but that image is not very prevalent among the people I speak to. Rather, they still think of the Erasmus programme (in which the UK no longer participates).

On the way back to my hotel at the other side of London, I pass through Erasmus Street, a leafy avenue, where the sound of primary school pupils emanates from Millbank Academy. For fun, I ask some passers-by about Erasmus, but people who live or work in Erasmus Street have no idea who this street is named after (“but then again, I’ve only been working here for six months”).